This article was first published in Beauhurst’s annual equity report, The Deal, under the title “The Hedge Fund-ification of Venture Capital”. It is now available on the Beauhurst blog.

We saw record equity investment in the UK in 2021, both in terms of the total amount invested and the number of deals. The country’s high-growth startups and scaleups secured £22.7b across 2,679 announced equity rounds, up from £11.3b across 2,283 rounds in 2020.

This increase in private market activity was repeated around the world as economic stimulus measures drove investors into riskier assets.

Traditionally, VC and PE firms have operated on distinct investment models from hedge funds; they are usually structured as closed-ended vehicles with investor withdrawals only possible at the end of a 10-year cycle. Hedge funds have operated an open-ended structure, allowing investors to move in and out of the fund based on shorter term performance.

Amid the frenzied shovelling of cash into private companies, some venture capital and private equity investors were behaving in new and intriguing ways, and it seems that the traditional 10-year venture capital fund lifecycle may finally be going out of fashion. It is being replaced by something more akin to a hedge fund structure. Beauhurst data can help shed light on why this is happening and why venture capitalists are facing more competition than ever before for deals.

01. A brief history of the venture capital investment model

In the book “VC: An American History”, Harvard Business School professor Tom Nicholas locates the emergence of the venture capital model in the approach to capital deployment that came to prominence with the rise of the American whaling industry in the 18th and 19th centuries. While the following 100 years or so saw the emergence of innovations such as the limited partner structure, Nicholas notes that the business model for venture capital has proved to be remarkably stable over time:

“…if one asks how exactly VCs do what they do, it is not clear that the answer today is much different from half a century ago. The dominant form of organization is still the limited partnership with an ephemeral fund life, even though this places constraints on the time scale of investment returns. Although there have been some organizational structure and strategy innovations, these have been paradoxically rare in an industry that finances radical change.”

Given the stability of the VC fund model through time, it was big news in the industry when US venture capital firm Sequoia Capital announced last year that it was moving to a permanent structure. In a Medium article announcing the shift, general partner Roelof Botha highlighted that the industry is stuck using a 10-year fund cycle that is no longer fit for purpose. Sequoia’s new structure has more in common with the open-ended structure typical of hedge funds. Botha noted that founders’ ambitions are not constrained to a 10-year period, so neither should Sequoia’s. Botha’s words echo those of Nicholas:

“Ironically, innovations in venture capital haven’t kept pace with the companies we serve. Our industry is still beholden to a rigid 10-year fund cycle pioneered in the 1970s. As chips shrank and software flew to the cloud, venture capital kept operating on the business equivalent of floppy disks. Once upon a time the 10-year fund cycle made sense. But the assumptions it’s based on no longer hold true, curtailing meaningful relationships prematurely and misaligning companies and their investment partners.”

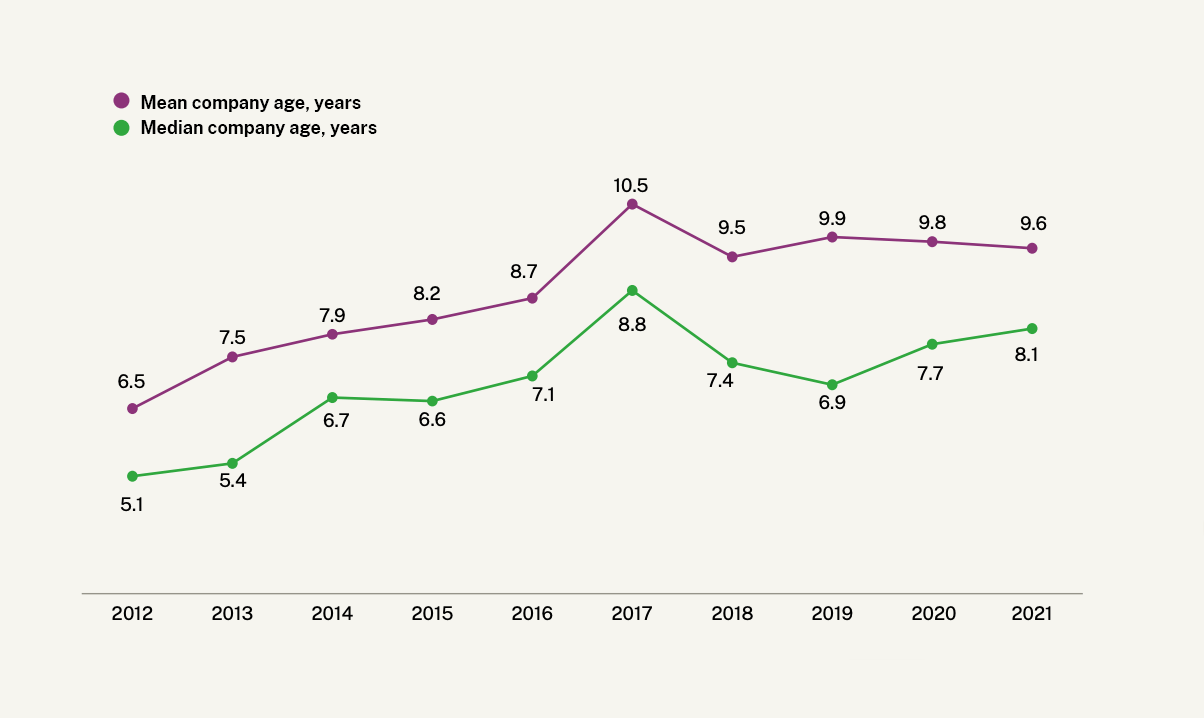

Beauhurst data over the last decade confirms that equity-backed companies in the UK are taking longer to achieve an exit, either through an initial public offering (IPO) or acquisition. Both the mean and median number of years from incorporation to exit for companies backed by venture capital and private equity firms have increased by around 50%. This shift among UK startup companies could be part of a global trend, causing the venture capital industry to reevaluate its business model.

From Beauhurst: Average time to exit from incorporation of first deal since 2012

02. Startups are taking longer to reach an exit

The increase in time to exit could be indicative of longer commercialisation periods for startups as the UK ecosystem matures. Entrepreneurs have arguably addressed many of the easier problems that can be solved via software or web-enabled business models. Early-stage companies may, therefore, be taking longer to achieve product-market fit and reach the scale and sustainability that make them attractive acquisition targets or suitable IPO candidates.

Changing dynamics in capital markets are also playing a role. Business owners are able to tap increasingly large sums of capital in the private markets, achieving a level of liquidity without needing to comply with the rigorous regulations that public companies are subject to.

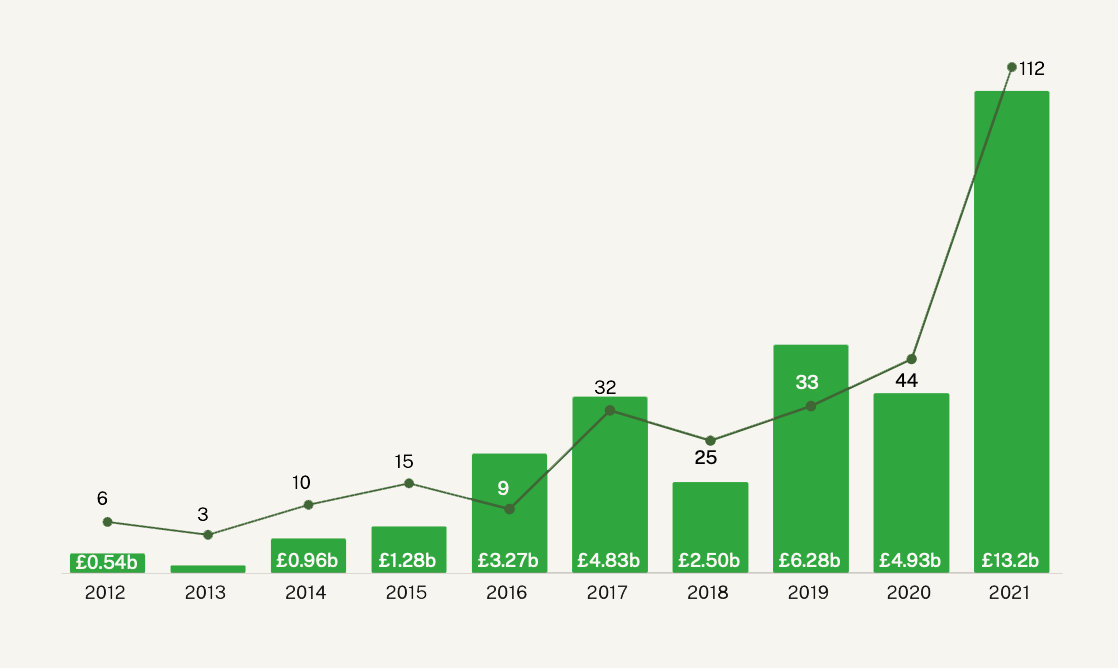

For many years we’ve noted the rise of megadeals—rounds where the invested amount is equal to or greater than £50m. Around 10 years ago, most companies could only hope to access such sums via public markets, but now venture capital and private equity investors are frequently participating in megadeals, with a record 112 completed in 2021.

From Beauhurst: Number of megadeals and amount raised since 2012

With so much capital available, VCs are also letting founders take chips off the table—allowing them to release some of the value of their shares via secondary transactions, without an exit event.

We know, anecdotally, that the number of secondaries occurring alongside primary transactions is increasing, though the full extent is still unknown due to difficulties separating the two in the data.

Both these factors—the increasing availability of private capital and more avenues for founder liquidity—are contributing to an increasing time to exit for equity-backed, mature companies. It may be that the confluence of these factors with increasingly lengthy technology and commercialisation cycles are causing companies to require more time to exit, pushing startup lifecycles beyond the traditional 10-year timescales that most VCs—and their limited partners—are familiar with.

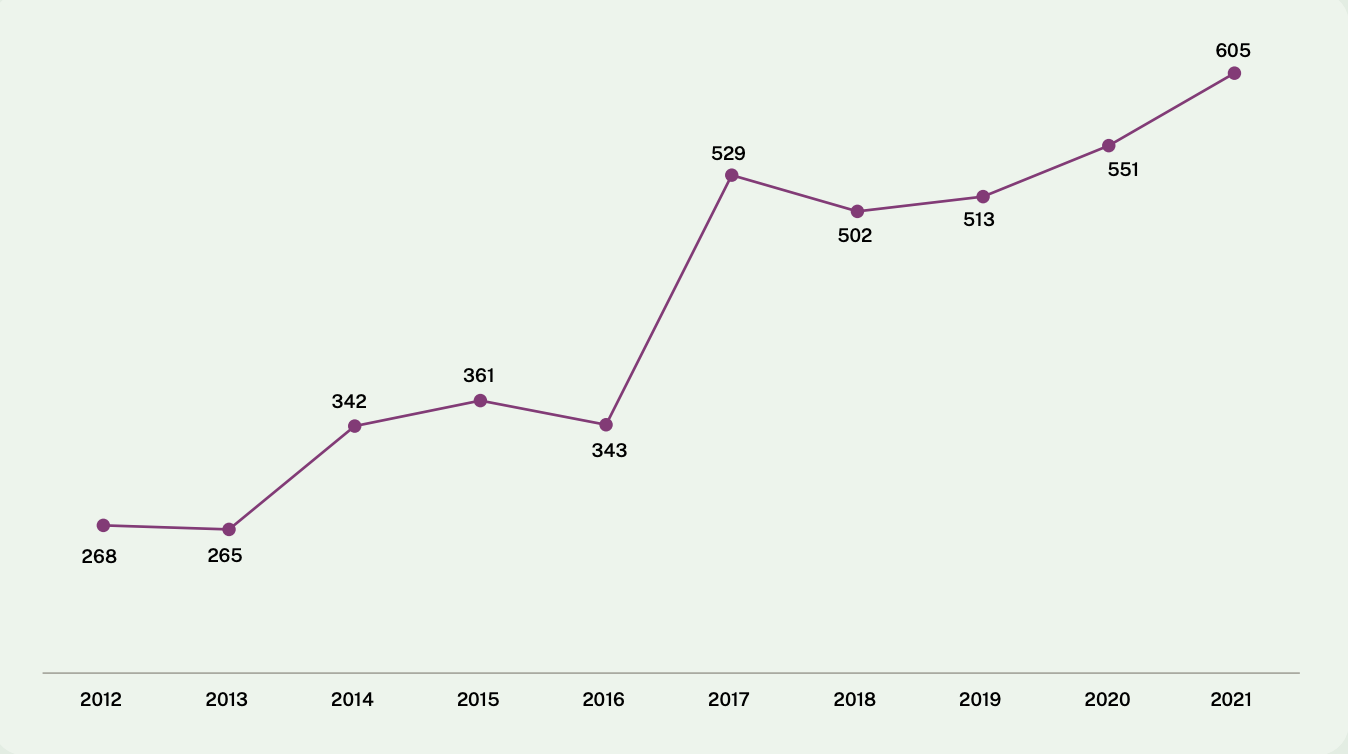

03. Competition amongst venture capital funds is increasing

While the changing behaviour of companies may be driving the reevaluation of the VC model, another factor at play is the increase in competition for equity stakes in private businesses. The number of new entrants providing equity finance to private UK businesses with high-growth potential has been on an upward trajectory since Beauhurst started collecting data more than a decade ago. In particular, the last five years have seen over 500 new backers become active in the UK market each year. This gives founders far more options for securing finance and means that VCs must compete more aggressively with their peers and other potential backers to win deals.

Number of funds investing in a UK business for the first time

The emergence of super allocators like SoftBank and Tiger Global makes more sense in an increasingly competitive environment. As Everett Randle, Principal at Founders Fund, lays out in his popular article on Tiger Global, the hedge fund has developed an attractive offering based on speed of capital deployment, high valuations, and light due diligence that traditional VCs will struggle to match.

So, while hedge funds are acting a bit like VCs to access startup returns, VCs are also starting to act a bit more like hedge funds, to access returns beyond the normal VC exit schedule. Consider some of the changes accompanying Sequoia’s new fund structure, as outlined by Botha:

“As part of this change, we are also becoming a registered investment adviser. This expands our flexibility to support our portfolio companies through various financing events, such as secondaries or IPOs. It also enables us to further increase our investments in emerging asset classes such as cryptocurrencies and seed investing programs.”

As a result of the changes at Sequoia, the firm will be able to invest in other asset classes beyond private equity and without defined exit horizons. Becoming a registered investment advisor with the US Securities and Exchange Commission means that Sequoia will no longer be bound by venture capital rules that require it to keep 80% of its assets in private companies. This step allows it to hold stakes in listed portfolio companies over the longer term. In effect, Sequoia has taken steps to make itself more like a hedge fund.

In the UK, 2021 was a record year for IPOs by equity-backed growth companies. High valuations driven by the increased relevance of tech during the pandemic, retail investor activity, economic stimulus measures, and changes to listing regulations have made public markets more attractive to companies and their backers. By shifting to more flexible structures, a new breed of VC firms will be able to hold onto stakes in portfolio companies even after they IPO. This could enable such VCs to benefit from significant public market uplifts in the value of portfolio companies that their more traditional peers are unable to tap.

The competitive dynamics of venture capital are changing—firms like Sequoia may be the vanguard of a new type of VC investing. Many VCs may soon be facing the same pressures as the companies they fund: adapt or die.